Bias versus Variance Explained

As most things in this blog will be, this entry attempts to explain bias vs variance the way that I found it to be the most clear and enlightening.

Fitting a model on simple data

Let’s start by building an intuition and seeing the relationship between bias/variance with over/underfitting. Machine learning models have an underlying complexity level that allow them to be more or less flexible while trying to represent the dataset. Let’s imagine a regression model trying to predict a dataset with just two values per row, X and Y. Y is the real valued label that we are trying to predict based on the value of X.

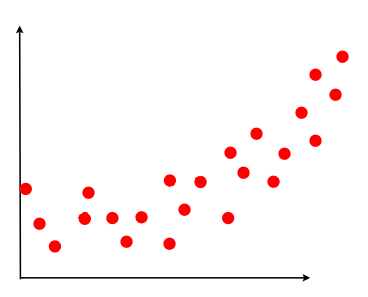

Let’s assume that our ground truth (what we are ultimately trying to predict) looks a bit like the following:

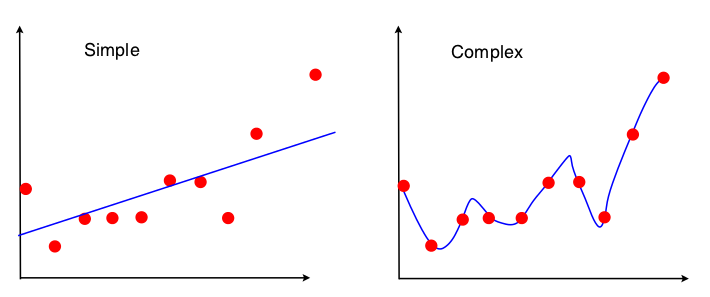

Now, most datasets can never truly represent the ground truth perfectly. In our case, we will take a sample of points, use it as a training set, and build our models with it. It could look like the following:

Two predictive models have been applied on the dataset. Each has its own characteristics and fits the data in a different way. Neither the simple nor the complex model are very correct, since one of them generalizes too much while the other is too precise.

Simple model

The simple model is linear, it can only fit data by drawing a line. Its precision on the training data is rather low. If this model could talk, it would say that the data has a lot of noise, and the underlying ground truth is in reality the line. That top right point is just an unlucky outlier. This model is clearly underfitting.

If we take a different sample of points (of the same ground truth) and train again, it would look almost the same. The same line can explain many different samples of the ground truth.

The error on this sample is quite high, since not many points are close to the line. But if we test the model with a test set, the error will be similar. The variance over different samples of the same ground truth is low. It also means the general error the model is a tradeoff to be able afford this low variance. Consequently, the bias of the model is high.

Complex model

The complex model is fitting a very high degree polinomial on the data, perfectly explaining each point. If this model could talk, it would be saying that the ground truth is a quite complex polinomial. This model is clearly overfitting.

If we take a different sample of points and train again, it would look very different. This polinomial perfectly fits the current sample, but doesn’t fit at all other samples of the same ground truth.

The error on this sample is very low, since all points sit on the line. This means its bias is low. But if we test it by using a test set, the error would be very high (even higher than the linear model!). It’s not biased towards some specific distribution or shape (like the line does); it will do whatever it takes to be unbiased and train itself with maximum precision. However, the variance of this model is very high. It needs to change a lot to be able to adapt to different samples.

Perfect model?

The arguably best model for this data would be one that takes a slight curve upwards, following the trend we could see in the first picture. However, in a real world dataset we don’t know what the ground truth looks like, so it’s extremely difficult to know what model works best.

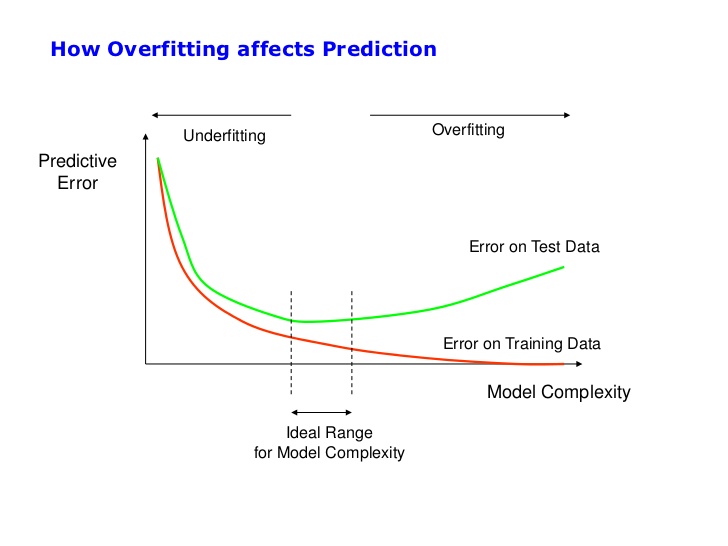

Bias / variance tradeoff

The way people usually deal with this problem when they have to build complex models is to keep an eye on both trainig error and validation/test error.

While they both fall proportionally, the model is still underfitting and could do better. However, once the test error behaves differently than the training error (usually going up again), it’s time to stop training because you will be overfitting from now on.

The source that helped me most was this excellent post by Scott Fortmann.

Please feel free to add comments if you liked this post or you think something is wrong or should be clarified.

Comments